"Be anything you want. Be madmen, drunks, and bastards of every shape and form. But at all costs avoid one thing: success." - Thomas Merton

"Be anything you want. Be madmen, drunks, and bastards of every shape and form. But at all costs avoid one thing: success." - Thomas Merton

As my extended family gathered around the Thanksgiving dinner table before the market crash in 2008, conversation with cousins flowed about friends making big money with technology start-ups: "more, more; faster, faster; bigger, bigger."

A hail of laughter greeted me when I quietly muttered that my ambition was, "poorer, poorer; slower, slower; smaller, smaller."

When Sojourners started in 1970, I was 23 years old. Seven young seminary students pooled $100 each and used an old typesetter that we rented for $25 a night above a noisy bar to print 20,000 copies of the first Post-American.

We took the bundles in our trucks and cars to student unions in college campuses across the country, and began collecting subscriptions in a shoebox kept in one of our rooms.

For more than a decade we lived with a common economic pot and allowed ourselves $5 a month for personal spending. The highest-paid staff person was a young woman from a neighborhood family who wanted an evening cleaning job.

We worshiped together twice a week and opened our homes to our neighbors. When our first son was born, we brought him home to a row house in Columbia Heights where we were living with 18 other people – including an African-American family and a Lakota couple with some of their extended family from the reservation in South Dakota.

You had to be a bit crazy to be in the early community. And yes, we were poor. And we were small.

We tried to slow down. I tacked to my office door Thomas Merton’s warning to social activists about the violence of overwork:

"To allow oneself to be carried away by a multitude of conflicting concerns, to surrender to too many demands, to commit oneself to too many projects ... is to succumb to violence. The frenzy of our activism ... kills the root of inner wisdom which makes work fruitful."

To stay alive, we needed prophet, pastor, and monk.

On our best days these three energies were at least on speaking terms with each other. But like every other community that I know, most of the time we majored in one, minored in a second, and had a hard time with the third.

For us, the outer journey of prophetic ministry was our major. The journey together in community was our minor. And the inner journey was our blind spot. We did not know how to be silent, or still, or slow. And so, like most young communities, we often could not see our own inner contradictions and arrogance, our own excesses and extremes.

Now, 40 years later, Sojourners has grown up. We are not poor, or small, or slow. We have a large budget with many full time staff. For better or worse, Sojourners has become an "institution" with the necessities of policies, procedures, protocols, precedents, and concerns about hiring and firing, supervision and management, promotions and salaries, lawsuits and litigation.

Some might say Sojourners is now a "success." We certainly have a bigger public microphone than we did in the past, and the message of faith-in-action that we have been pushing for 40 years seems to be taking root.

It all boils down to this: Poorer, slower, smaller may be necessary for the inner journey, but it is not a very good business plan.

In Falling Upward, Richard Rohr talks about the journey of descent that characterizes “second-half-of-life” spirituality. He reminds us that institutions by nature are "first-half-of-life structures" that "must and will be concerned with identity, boundaries, self-maintenance, self-perpetuation and self-congratulation." He goes on to caution against false expectations:

"Don’t expect or demand from groups what they usually cannot give. Doing so will make you needlessly angry and reactionary."

In Bill Plotkin’s model of the eight stages of human development in Nature and the Human Soul, institutions can, at most, be stage four, which in his view is still an adolescent level. In his opinion, only 15 percent of Americans have crossed into mature, initiated adulthood, and in general we are stuck in a pathological-adolescent culture that lacks the wisdom of initiated men and women elders.

An institution’s job is to encase the renewal insight in a preserving shell that can carry the renewal seed to a future generation — and not to die to their organizational identity, which is required to begin Plotkin's stage five.

If we are lucky, we outgrow the organizations that we ourselves give birth to and become "joyfully disillusioned" with the very institutions that we help to create. And if we are wise, some of us will grow by staying within the very organizations that we ourselves have outgrown.

The tension of this seeming contradiction is the transformational stew of new possibilities, both for the individual who stays and for the organization. We should not expect the institution to be more that it can be.

In some ways we no longer "believe" in the organization, but we do pin our hopes to the renewal energy that birthed it, and keep letting that spirit renew us. Then we can stand in the midst of organizational disappointments and betrayals, of silliness and pettiness. Broken dreams and relationships do not need to destroy us. Instead, with consciously applied inner work, they can become small doors that lead to greater wholeness.

It takes a contemplative mind to see one’s own inner contradictions, the failures and inherent betrayals within our own lives and the institutions that we help to create. Those who take this journey of descent into their own sacred wound understand that what is flawed in them is somehow intimately connected to the unique gift that they have to offer to a broken world.

Shadow work becomes a necessary spiritual discipline. Seeing in themselves what they dislike in the other, they learn to be gentle and kind.

They delight in vulnerability and weakness, and believe that the wisdom that comes from their mistakes and failures is worth passing on to younger communities and movements.

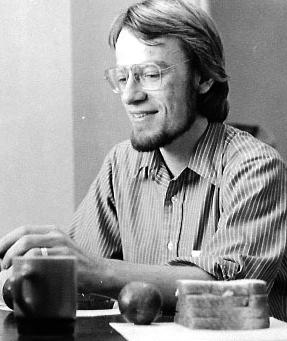

Bob Sabath is Director of Web and Digital Technology and one of the founders of Sojourners. He now lives with his wife Jackie at the Rolling Ridge Study Retreat Community in West Virginia, where he offers spiritual direction and wilderness retreats. He delights in teaching his grandchildren to introduce him as: “my grandpa: he can do everything – except the one thing necessary.” Bob wants everyone to know that he is still a mess, but at least he knows it.

Editor’s Note: These reflections were birthed by a three-day desert journey in Arizona where Bob lived with Rainer Maria Rilke’s poem, “The Man Watching.” You can read the poem and listen to his son Peter’s musical rendition HERE.

Further Resources: